I still remember the thrill of moving from my trusty Brother electric typewriter to a remote computer terminal. I’d type out a paper at the University of Calgary, send it across campus to the printer station, and — assuming someone was there — I’d find my term paper neatly placed in a pigeonhole. No more whiteout, no more misaligned type. Just a professional looking report. It felt like magic.

Back then, the future was something we saw on TV. In the 1960s and 70s, Star Trek imagined a world where Captain Kirk could simply ask the ship’s computer a question and get an instant, logical response. That seemed centuries away.

But here we are today where artificial intelligence (AI) can answer your questions in real time, scanning vast databases for what it thinks is the best response. Not perfect — just reasonable. Still, it feels like magic.

I’ve written before about AI’s potential in school (The Sky is Falling … AGAIN, Jan 2023) — personalized instruction, student assessment, lesson generation. But it’s not just about teaching and learning. AI has the ability of transforming the business side of K–12 as well — student registration, policy or procedure inquiries, workflow improvements, even analyzing population growth trends. And that’s only scratching the surface.

THE VISION: Harness AI to improve student learning and success while limiting misuse and risk.

AI is everywhere — digital assistants, search engines, social media, online shopping, fraud prevention, gaming, medical diagnosis. The list goes on. But with this leap forward come real concerns: deepfakes, bias, privacy violations, job security, hacking, intensive energy consumption and more.

So, where do schools fit in? How do we balance possibilities with risks?

To begin, we keep asking the important questions:

- What bias and accuracy does this AI tool bring?

- Does it make sense to use it in a particular place? Will it improve student access to their learning?

- How do we protect data privacy?

- How do we preserve critical thinking skills?

- How do we keep human connections at the center?

Actively exploring its possibilities is not only important, it’s also non-negotiable. As AI’s capabilities evolve, waiting until ‘things have settled’ is like waiting for the grass to stop growing before you mow it. You might as well start now, because it’s only going to get more difficult the longer you wait.

We’ve done this before. Think calculators. Think the internet. Both were disruptive. Both raised concerns. Yet we found ways to integrate them without losing the essence of learning. Calculators didn’t erase math skills. The internet didn’t destroy originality — plagiarism existed long before Google. We adapted. We can do it again.

My point here is not to minimize the real and potential risks of AI — they are there — but, instead to chart a path of exploration that can maximize its advantages while minimizing the risks. Yes, there are bigger challenges with AI than with the calculator and the internet — primarily because AI is evolving so quickly, and we don’t know what next month will look like, let alone next year. Yet, it’s potential for improved access to curriculum, personalizing the educational experiences, building student success, and enhancing the business side of education is unparalleled.

Why AI Matters for Kids’ Brains

Can technology actually help our kids’ brains grow? Yes, if we use it wisely.

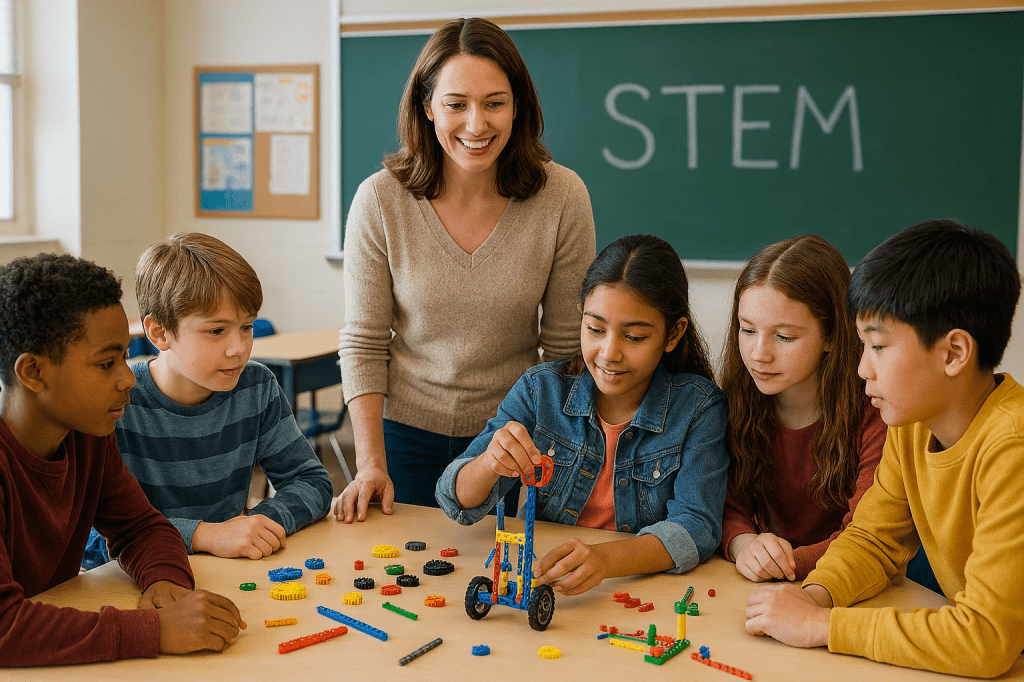

Here’s the good news — AI can be a powerful ally for brain development. AI can personalize learning, offering challenges that match a child’s pace and providing instant feedback. Research shows this supports executive functions like working memory and cognitive flexibility. When used wisely, AI can help teachers focus on what they do best — inspiring curiosity and connection.

But here’s the catch — too much automation can strip away the human connection that fuels motivation. Brains aren’t just processors — they’re social organs. Kids need eye contact, laughter, and human connection. Schools are where this happens. When I ask students what’s working for them, they never say “the technology”. They talk about teachers, administrators, counselors, educational assistants—the people who connect with them on a daily basis.

Human connections build confidence, understanding and competence — technology is a tool, not the teacher.

Of course, every shiny tool has a shadow. Over-reliance on AI can lead to passive learning, reduced creativity, and data privacy concerns. AI algorithms aren’t perfect — they carry biases that affect their output, so teaching about these potential biases help us manage how and where we use the tool.

So, what’s the solution? Balance.

Digital leadership means creating guardrails so AI enhances — not replaces — the human elements of learning. Think of AI as the sous-chef, not the head chef. It can chop the veggies, but the teacher still crafts the recipe. In Saanich, as part of our own guardrails we developed an Artificial Intelligence Framework built on four themes:

- Teaching & Learning

- Inclusion and Accessible Learning

- Ethical Use

- Privacy, Security & Safety

What Can Parents Do?

You don’t need a tech degree to stay involved. Encourage screen-time boundaries. Promote activities that build executive function outside of the tech world — things like puzzles, outdoor play, and storytelling. The best brain development happens when kids combine digital learning with real-world experiences — with trusted adults being the glue and the motivation.

AI in education isn’t a villain or a superhero — it’s a tool. In the hands of thoughtful leaders and engaged parents, it can help kids develop the cognitive skills they need for a complex world. But, we’re also not losing sight of the human heartbeat in learning.

Because, no algorithm can replace the magic of a teacher who believes in your child — or the joy of a parent cheering them on.

(This post was written by the author. AI created some of the images as well as reviewing the post for flow and grammar.)