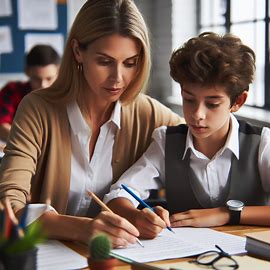

In every classroom — at every grade level — a quiet tension exists between correction and encouragement. As educators, we find ourselves navigating the delicate balance between offering constructive criticism and celebrating effort.

Can well-meaning praise sometimes do more harm than good? Is that possible?

An article in Forbes magazine, “Criticism Is Good, But Praise Is Better,” reminds us that while feedback is essential, the tone and intent behind it can shape a student’s confidence and motivation. I recently wrote a blog post about Confirmation Bias (Why Students and Adults Struggle to Be Wrong — and How to Help, Dec 2025) where I outlined the vulnerability of students whose self-image is still developing and can be inadvertently and negatively influenced by both praise and criticism.

The way we speak to students can dramatically influence not just their academic outcomes, but their belief in themselves. Finding the balance — or sweet spot — for optimal personal growth is tricky.

When used well, praise is a powerful motivator. A teacher once told me how her classroom transformed when she shifted from pointing out mistakes to highlighting effort: “I started saying things like, ‘I noticed how you kept trying even when the problem was hard.’” The result? Students became more engaged, more curious, and more willing to take risks.

But, not all praise is created equal.

When praise becomes automatic or overly general — “Great job!” or “You’re so smart!” — it can lead to Confirmation Bias, where students begin to seek validation rather than growth. They may cling to familiar strategies, even when those strategies aren’t working, simply because they’ve been praised for them in the past.

A student praised repeatedly for their vivid vocabulary might resist feedback about their sentence structure. Why change what’s already being celebrated? In these moments, praise can unintentionally close the door to deeper learning.

So, it’s important to recognize that giving praise runs the risk of actually stifling creativity and broader thinking.

That’s why the most effective praise is both specific and reflective. Effective praise acknowledges what’s working while gently inviting students to consider alternatives. For example: “I love how you used descriptive language here. What do you think would happen if you varied your sentence lengths to build suspense?” This kind of feedback affirms effort while encouraging exploration. It minimizes the risk of contributing to confirmation bias.

Parents can adopt this approach at home, too. Instead of saying, “You’re amazing at math,” try, “I noticed how you broke that problem into steps—that strategy really worked. What might you try next time if it gets trickier?” This not only builds confidence but also fosters a mindset of adaptability and growth.

Ultimately, the goal isn’t to either eliminate criticism or flood students with praise.

It’s to create a culture of thoughtful feedback — striking a balance where students feel safe to take risks, reflect on their choices, and revise their thinking. When we do this, we’re not just helping them succeed in school. We’re helping them become resilient, reflective learners for life.

So, praise wisely, correct with care, and you’ll keep the door open for personal growth.